How To Maintain Muscle Power as We Age

We chat with Dr. Damien Callahan about the power of physical activity in building fast-twitch muscle fibers across the lifespan. Part 1 of our series on muscles and aging.

October 17, 2023

Damien Callahan, PhD

Dr. Damien Callahan is an assistant professor of human physiology at the University of Oregon. He has a PhD in kinesiology from the University of Massachusetts, Amherst, where he studied age-related differences in muscle fatigability.

Anne Broussard

Anne Broussard is a Professor Emerita at the University of New Hampshire. She has race-walked in all 50 states, completed over 100 marathons, and continues to stay active in retirement.

Meet Anne Broussard — a woman who at the age of 70 is still competing in marathons. Or to be precise, she is race-walking them. Her marathon journey began at 55 years old after she recovered from breast cancer and her oncologist encouraged her to pick up a sport. Fast forward to today, and Anne is about to complete her 110th marathon.

“I didn’t mean to do all that!” joked her oncologist when they last met, but Broussard has no intention of stopping anytime soon. “I will continue to stay active for a long time,” said Broussard.

Race-walking is an Olympic track and field event where athletes walk faster than most people can run. The world’s best race-walkers can complete a mile in under 6 minutes. Although Broussard is not an Olympic athlete, she works with a coach to perfect her technique and form. She has now race-walked in all 50 states and participated in international marathons in France, Italy, and Spain.

To continue to push her limits and do the sport she loves, Broussard supplements her cardio with weight training. She even comes up with creative ways to engage her fast-twitch muscles when traditional exercises like box jumps are too harsh on her knees.

While it’s common to doubt our physical strength and abilities as the years go by, there are many ways to maintain strength and mobility. Aging comes with various factors that contribute to muscle loss — such as hormonal changes, illness, injury, and nutrition — but one of the most significant culprits is inactivity.

Left: Broussard completing her second Rome marathon in 2013. Right: Broussard completing the Loco Half Marathon last October, 2022. Credit: Anne Broussard

Age-Related Loss of Muscle

Sarcopenia is the age-related loss of muscle mass and strength. While the average person starts to experience muscle loss in their 30s, the most notable decline tends to occur in the late-50s.1,2 If consistent training is not maintained, muscle strength and mass can shrink by 10% to 15% per decade after the age of 50.3,4

Why do we lose so much muscle as we age? “Muscles cannot be separated from our nervous system,” said Dr. Damien Callahan. “As much as I’m a card-carrying muscle physiologist, I do sometimes tacitly recognize the existence of a nervous system,” he joked. “This is one of these cases where the nervous system is leading the show from an aging perspective.”

When motor neurons in the brain and spinal cord become inactive, the muscle fibers they once controlled either get reassigned to another existing motor unit or they fade away altogether. No more is this true as we age than for fast-twitch muscle fibers, which we lose at a faster rate compared to our slow-twitch muscle fibers.

Fast- Vs. Slow-Twitch Muscles Fibers

Slow-twitch fibers are more endurance-oriented and are better suited for activities like long-distance running. Fast-twitch fibers are responsible for rapid, powerful movements such as sprinting or jumping, but they also fatigue more quickly than slow-twitch fibers. It’s important to note that fast-twitch muscle fibers contribute the most to the production of muscle power. This is significant because muscle contractile power predicts physical function5 better than strength, and both predict morbidity/mortality in older adults.6 The distinction between muscle power and strength lies in the fact that power is determined by both force and velocity, whereas strength does not depend on velocity.

Studies have shown that the preferential loss of fast-twitch muscle fibers can significantly impair the ability of older individuals to generate muscle force and power, which can lead to an increased risk of falls. For instance, a study found that 15 elderly women with hip fractures had significantly smaller fast-twitch muscle fibers in the vastus lateralis – the largest, most powerful quadricep muscle in the thigh that’s crucial for overall stability – compared to healthy, elderly women. As expected, both groups of older women had smaller fast-twitch fibers compared to young, healthy women.7

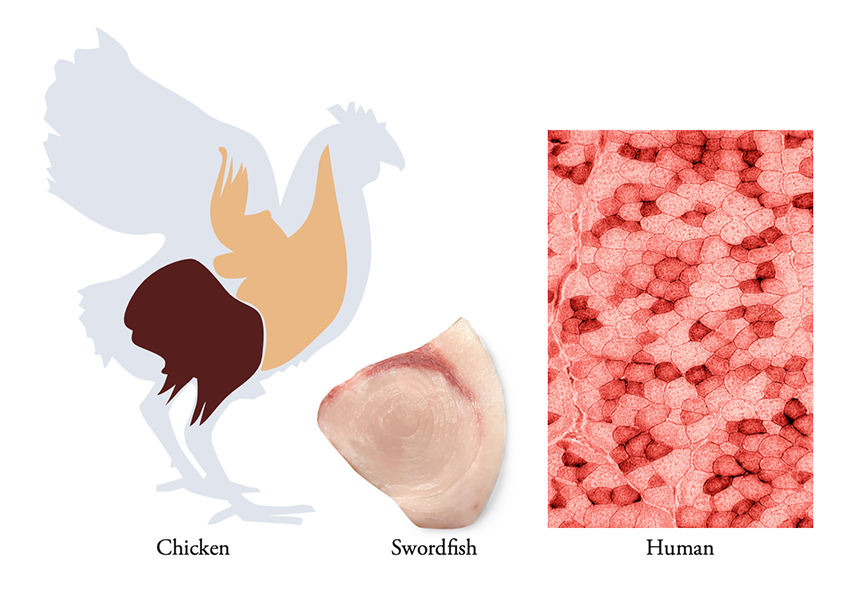

Certain muscles in chickens and fishes consist mainly of fatigue-resistant, slow-twitch fibers, commonly referred to as “dark meat,” while other muscles consist of fatigable, fast-twitch fibers, known as “white meat.” In contrast, in humans and other mammals, different fiber types are mixed and distributed within each muscle. Image of human fibers stained to show different fiber types. Courtesy of Richard Lieber. David Delp | Biomechanics of Movement.

Why Do We Lose More Fast-Twitch Fibers As We Age?

Most daily activities don’t demand these fast-twitch fibers, and as we age, physical activity tends to decrease, reducing the need for them. To activate fast-twitch muscle fibers, a certain level of heavy resistance is necessary.

For example, when lifting a weight, our arm first engages the slow-twitch muscle fibers. To curl a weight well below your maximum ability (for example, 2 pounds if the most you can curl is 20 pounds), only slow-twitch fibers are necessary. However, when the weight approaches maximum effort (15 pounds for the person in our example), slow-twitch fibers are activated at first, but then fast-twitch fibers are needed to generate necessary force to complete the bicep curl.

“The principle of ‘use it or lose it’ applies here,” said Dr. Callahan. “Consistent physical activity is the best prescription for an older adult interested in maintaining their neuromuscular function.”

How heavy is "heavy"?

Words have different meanings for different people. Be sure you understand the nuances when you’re reading up on performance research. For the purpose of this article, a “heavy” weight is one where you can only complete the 1- to 5-reps and a “moderate” weight is in the 6- to 15-rep range. These numbers may vary slightly across studies.

How To Increase Fast-Twitch Muscle Strength?

A key factor in growing or maintaining fast-twitch muscle fibers is ensuring their activation. Both heavy and moderate-weight training approaches can increase fast-twitch muscle fibers as long as fatigue sets in. The goal is to exhaust the slow-twitch fibers so that fast-twitch fibers are needed to sustain the muscle force production.

In fact, a 2021 review and meta-analysis on a young population of participants found that if your goal is to get stronger, then heavy- and moderate-load training increase strength more than light-load training, even when light training is performed to muscular failure.8 If your goal is to get bigger muscles in size, though, then load doesn’t matter as long as you train to fatigue.9 But what if moderate weights are not possible due to health concerns?

“In the end, the reason to use low loads in older adults especially is to obviate concerns over osteoarthritis-associated discomfort or orthopedic injury,” said Dr. Callahan. “If that’s the guiding principle, the fact that high-load training improves strength slightly more is moot. The best exercise is the one that you’re most likely to engage with on a consistent basis. If low-load resistance training lets folks do it more frequently with less injury, that’s the preferred way to go.”

Context matters when it comes to strength gains

When applying findings from muscle research, Dr. Callahan reminds us: “Practically and clinically speaking, strength gains are often very specific to the method of assessment. For example, training results seen with isometric contractions don’t transfer well to dynamic and vice versa. It’s possible using high loads in training helps volunteers perform better in 1 rep max assessments more than low load might. It’s not clear how that would translate to whole body function (where load is not selected by the individual, but thrust upon them by the circumstance).”

How To Increase Power

Muscular power is the ability to generate significant force rapidly. This type of movement primarily relies on fast-twitch muscle fibers, which can be engaged through rapid and explosive exercises like jump squats.

To increase power, Roger Fielding from Tufts University and colleagues designed a study that involved older women performing leg presses as fast as possible, 3 times a week for 16 weeks. They found that high-velocity resistance-training has a greater impact on increasing muscle power in older women than low-velocity.10 While the possibility of nervous system retraining couldn’t be ruled out, the results suggest that high-velocity training can enhance muscle power. Similarly, Dr. Callahan and his colleagues observed the same outcome in both men and women when measuring power during leg press exercises.11, 12

That’s all good and fine, but what if some of these power exercises are beyond your capabilities? This is where a touch of creativity can come in handy. Just like Broussard, you can try to find alternative solutions. Broussard has developed workarounds for her weight training, which she does twice a week while keeping up with her race-walking practice.

“I can’t do box jumps because it hurts my knees,” said Broussard. “I use what looks like a little trampoline and jump on that. I also can’t do lunges very well either. So instead I have rings that my husband mounted on the ceiling. I use the rings to get down into a lunge. I can also grab the rings if I need help getting up.”

Broussard also does leg lifts and clam shells. “Sometimes, as we get older, we also are more prone to tripping and falling. So I work on stabilizing those muscles in the knee.”

Training Tip

There are two main ways you can increase the performance of fast-twitch muscle fibers. First, increase the load of the weight to engage fast-twitch muscle fibers. For example, choose a “moderate” weight that enables you to do the exercise in the 6- to 15-rep range. Second, incorporate power moves into an exercise routine, if possible to do safely.

How Often Should Older People Workout?

In 2017, Marcas Bamman, a researcher from the University of Alabama at Birmingham, took on the intriguing question: How often should older individuals (aged 60 to 75) workout per week? To find out, Bamman compared the effectiveness of high-intensity (H) and low-intensity (L) workouts as well as their frequency for older populations.

Surprisingly, the results showed that the most effective number for leg muscles was two high-intensity and one low-intensity workouts per week (HLH). Those who performed three high-intensity workouts per week (HHH) actually had less muscle mass and strength compared to the HLH group. This could be attributed to longer muscle recovery time and enduring inflammation. Interestingly, the best approach for overall arm strength is a high-intensity workout three times a week (HHH), raising the potential that the best approach may be muscle-group specific.13

This meta-analysis seems to support Bamman’s findings but found limited number of high quality studies on the topic. Rigorous experiments designed to prescribe optimal exercise dose in older adults remain a sorely needed area for future research.14

Mediteraneo/Adobe Photos

Training Tip

To achieve greater muscle mass and strength, consider a workout regime that involves high-intensity sessions twice a week and a low-intensity session once a week for legs (HLH) and high-intensity sessions three times a week for arms (HHH).

“Remember you don’t need a gym,” said Dr. Callahan. “You don’t need a fancy piece of equipment. Your body weight is a great resistance tool, especially for the folks where that’s a real challenge and a barrier. Find a safe, comfortable, stable chair and do repeated chair rises from it. That’s a cardiac workout and a muscle workout all in one. And when you’re done, you’re already sitting down. You have a place to rest.”

Dr. Callahan is also keen to emphasize that “although consistency is key, it’s also never too late to begin your fitness journey. Humans are adaptable creatures, and our skeletal muscle tissue is highly resilient, even in older adults.”

Broussard concurs. “Where and when I grew up, there were no athletics for girls,” said Broussard, who only began swimming lessons in college. “And then in 2002, I had breast cancer, and they got it early.” Only in her fifth decade did she begin her marathon journey.

Broussard’s passion for fitness has also given her the opportunity to travel and explore new places. As she says, she is not just race-walking marathons; she is also walking towards a healthier, better quality of life.

Flash Q&A with Anne Broussard

What does strength mean to you?

Strength means doing what I want for longer. A good quality of life in my older years.

Favorite marathons?

Catalina Island, California. You get up at 4am and you take a ferry boat to the other end of the island. You race over the top of the island as the sun is rising. It’s just the coolest. Another favorite is Rome, Italy, because you race past historic sites.

Unusual sports moment?

I did a marathon in Eisenhower, Kansas, and the road was melting my shoes.

Flash Q&A with Damien Callahan

How do you stay active?

I cycle to work on most days. I work it into my daily activities. We have triplet 5 year olds. When I drop them off to preschool, they get on the cargo bike and we all ride together.

Do you have a favorite place you’ve biked?

For our honeymoon, my wife and I followed the Tour de France around. I rented a bike out there and did the summits of Col du Tourmalet and Luz Ardiden, all these famous Pyrenees climbs that the race goes over. Oregon also has just amazing biking. There’s an annual event–they call it Ride the Rim around Crater Lake, and they shut it down to auto traffic.

Get Deeply Researched Insights on Human Performance

Join our mailing list to get actionable performance tips and nuanced explanations of the science.

Citations

- Janssen, I., Heymsfield, S.B., Wang, Z.M., et al. Skeletal muscle mass and distribution in 468 men and women Aged 18–88 Yr. Journal of Applied Physiology, 89(1), 81-88 (2000). https://doi.org/10.1152/jappl.2000.89.1.81.

A snapshot in time

This publication is from 2000, which means the age-related decline observed in muscle mass could have increased or decreased since then. The findings should also be interpreted with caution due to the inherent limitations of cross-sectional studies. A cross-sectional study is a type of observational study that analyzes data from a population at a certain point in time.

- Melton III, L.J., Khosla, S., Crowson, C.S., et al. Epidemiology of sarcopenia. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society 48(6), 625–630 (2000). https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1532-5415.2000.tb04719.x

- von Haehling S., Morley J.E., Anker S.D. An overview of sarcopenia: facts and numbers on prevalence and clinical impact. J Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle 1(2), 129-133 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13539-010-0014-2

- Wilkinson, D.J., Piasecki, M., Atherton, P.J. The age-related loss of skeletal muscle mass and function: measurement and physiology of muscle fibre atrophy and muscle fibre loss in humans. Ageing Research Reviews 47, 123-132 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.arr.2018.07.005

- Bean, J.F., Leveille, S.G., Kiely, D.K., et al. A comparison of leg power and leg strength within the InCHIANTI study: which influences mobility more? The Journals of Gerontology: Series A 58(8), M728–M733 (2003). https://doi.org/10.1093/gerona/58.8.M728

- Losa-Reyna, J., Alcazar, J., Carnicero, J., et al. Impact of relative muscle power on hospitalization and all-cause mortality in older adults. The Journals of Gerontology: Series A 77(4), 781–789 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1093/gerona/glab230

- Kramer, I.F., Snijders, T., Smeets, J.S.J., et al. Extensive type II muscle fiber atrophy in elderly female hip fracture patients. The Journals of Gerontology: Series A 72(10), 1369–1375 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1093/gerona/glw253

- Lopez, P., Radaelli, R., Taaffe, D.R., et al. Resistance training load effects on muscle hypertrophy and strength gain: systematic review and network meta-analysis. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 53(6), 1206-1216 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1249/MSS.0000000000002585. Erratum in: Med Sci Sports Exerc. 54(2):370 (2022).

- Grgic, J. The Effects of low-load Vs. high-load resistance training on muscle fiber hypertrophy: a meta-analysis. J Hum Kinet. 31(74),51-58 (2020). https://doi.org/10.2478/hukin-2020-0013

- Fielding, R.A., LeBrasseur, N.K., Cuoco, A., et al. High-velocity resistance training increases skeletal muscle peak power in older women. J Am Geriatr Soc. 50(4), 655-62 (2002). https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1532-5415.2002.50159.x

- Reid, K.F., Callahan, D.M., Carabello, R.J., et al. Lower extremity power training in elderly subjects with mobility limitations: a Randomized controlled trial. Aging Clin Exp Res. 20(4), 337-43 (2008). https://doi.org/10.1007/BF03324865

- Reid, K.F., Martin, K.I., Doros, G., et al. Comparative effects of light or heavy resistance power training for improving lower extremity power and physical performance in mobility-limited older adults. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 70(3), 374-80 (2015). https:doi.org/10.1093/gerona/glu156

- Stec, M.J., Thalacker-Mercer, A., Mayhew, D.L., et al. Randomized, four-arm, dose-response clinical trial to optimize resistance exercise training for older adults with age-related muscle atrophy. Exp Gerontol. 99, 98-109 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.exger.2017.09.018

I'm an older adult, so this study's findings apply to me, right?

This study intentionally selected older adults who were relatively healthy and had minimal disease risks. Without further investigation, it remains uncertain whether the findings can be generalized to all older adults, for example, those with comorbid conditions, including mobility limitations, or who are taking certain medications.

- Borde, R., Hortobágyi, T., Granacher, U. Dose-response relationships of resistance training in healthy old adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Sports Med. 45(12), 1693-720 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40279-015-0385-9

How strong are the conclusions of a meta-analysis?

Meta-analyses are performed for systematic reviews of the scientific literature, but the strength of their findings rely on the quality of the studies included in the analysis. In this meta-analysis, the authors note that studies included in the review were mostly of low quality due to concerns regarding the randomization process and measurement of the outcome. The team tried to minimize that bias by performing a subgroup analysis using only the highest quality studies. Also, the meta-analysis included studies that mostly had young participants. Therefore, they recommend caution when extrapolating these findings to different populations without considering potential variations and limitations.

Playbook Terms of Use & Copyright

©2023-2024