Hydrating for Athletic Performance

Sports dietitian Marily Oppezzo explains how hydration affects physical performance and offers practical tips for staying hydrated.

September 26, 2024

Marily Oppezzo, Ph.D., M.S., R.D.N.

Dr. Marily Oppezzo is an instructor of medicine who is currently advancing her career through a mentorship program at the Stanford Prevention Research Center. She is also a registered dietitian, with her Masters in Nutritional Science and over two decades of experience teaching, coaching, and researching nutrition and exercise.

As a sports dietitian, Dr. Marily Oppezzo should have known better. A few years ago, she ended up in the emergency room because she forgot to carry water during a long, hilly run in 104-degree heat. She then made matters worse by guzzling water without consuming anything salty. The result: hyponatremia, an abnormally low sodium concentration in her blood. The symptoms included vomiting, extreme confusion, and brain swelling. Doctors gave her a hypertonic (i.e., salty) solution that saved her life.

In hyponatremia, Oppezzo explained, water moves into our cells making them expand and, eventually, burst. At the other extreme, hypernatremia can occur with extreme water loss, leaving behind too much sodium in the blood so that water is drawn out of cells and into the bloodstream, causing our cells to shrink. Either extreme can be deadly.

But how can you both hydrate to ensure optimal performance and avoid hydration-related illness?

Canva pro images

The answer is complicated, Oppezzo said. Our hydration needs depend on who we are – our gender, age, body size and composition, and personal sweat rate.1 And then there are the external factors: our sport’s exercise intensity and duration, the clothes we wear while exercising, environmental conditions (including whether we are acclimatized to those conditions), and the availability of fluid during a long event.1,2

“Guidelines have to come with a huge asterisk that’s bigger than the guidelines themselves, because we’re all unique snowflakes,” Oppezzo said.

In this article we explore the connections between hydration and athletic performance and outline the recommended guidelines for appropriate hydration, as well as how to tweak them to meet one’s personal needs.

The dangers of overhydration

Proper hydration during exercise is crucial, but drinking too much or too little can have serious consequences. If you start to experience symptoms like nausea, vomiting, headache, confusion, drowsiness, irritability, or swelling (edema), it may be a sign of hyponatremia, which can occur with drinking too much water and requires medical attention.

How Dehydration Affects Athletic Performance

During exercise, our bodies heat up as our heart rates increase to provide more oxygen to working muscles. To regulate body temperature, we sweat and breathe hard – losing water in the process. Water loss reduces our blood volume, which further taxes the heart, makes exercise seem more difficult, and causes fatigue.1,3,4 Dehydration also reduces our ability to regulate body temperature and depletes our glycogen reserves, which are a key resource for endurance athletes such as long-distance runners, Oppezzo says.1

“When you dehydrate, your heart rate increases because you’re losing blood volume – not because you’re working harder – and that’s going to affect your performance,” Oppezzo said.

How much dehydration is problematic? At two percent body weight loss, dehydration has a significant impact on athletic performance, as assessed by metrics such as time to exhaustion, perceived exertion, reduced strength and power, and changes in cognitive performance (reaction time, short-term memory and mood).2-7

Canva Pro Images

Hydration Guidelines for the “Average” Athlete

It’s important to consider hydration not only during and after a workout, but also before it.6-8 Ideally, you are drinking fluids regularly throughout your day to stay hydrated. The goal is to be comfortably hydrated before you exercise, Oppezzo said.

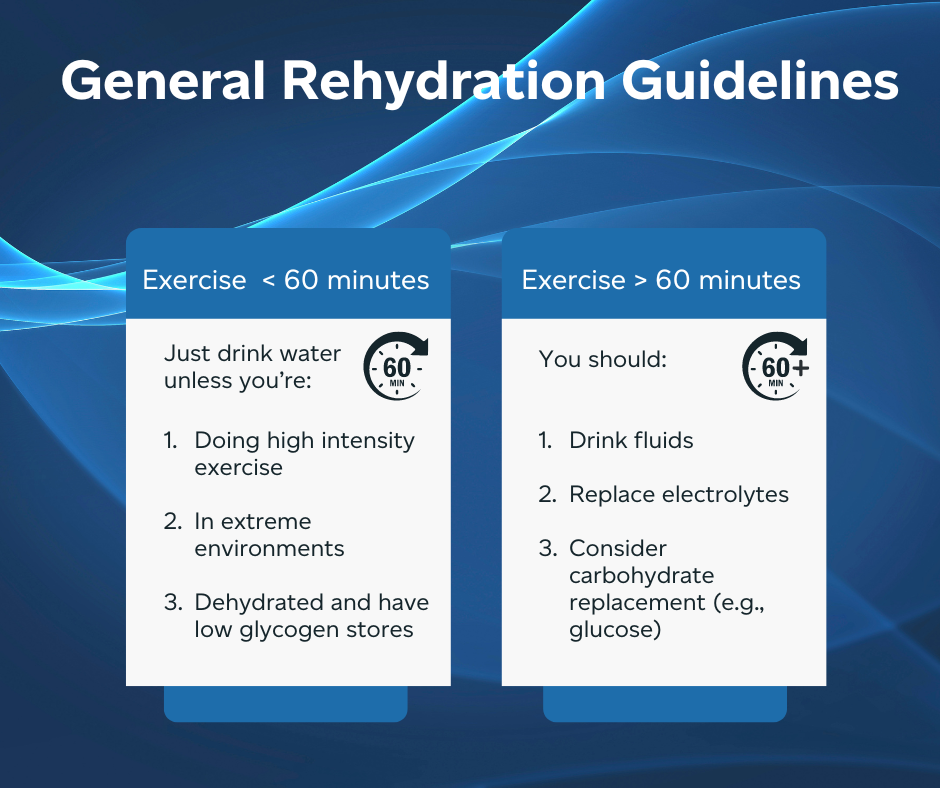

During exercise, the goal of hydration is to replace lost fluid and electrolytes – minerals like potassium, calcium, magnesium, and phosphate, as well as salt – so that you avoid a two percent drop in body weight.6-8 Various organizations have offered different guidelines, ranging from 2 to 8 cups (0.5 to 2 L) slowly ingested per hour.6,9 But this range is so broad that it’s not terribly useful and these guidelines don’t take into account body size and sweat rate, Oppezzo says.

Some in the sports community utilize a formula, sometimes referred to as the Galpin equation, that accounts for body weight:

Body weight (in pounds) divided by 30 = the number of ounces of water you should consume every 15 minutes during exercise

It appears to be based on a 1996 study of eight young women and men that compared time to exhaustion while running on a treadmill under two conditions: while consuming zero water and while dosing with water at levels determined by the equation above.2 “Since this guideline appears to be based on a single study of young people with similar body types, we can’t know if it would provide adequate hydration for the general population or in different environments,” Oppezzo said.

What does the Galpin equation research really test about hydration and endurance?

The 1996 study by Fallowfield et al.2 didn’t aim to find an optimal hydration formula. It does provide evidence that hydration improves endurance in the specific population and conditions studied. However, since it compares only one level of hydration with none, it doesn’t address how other hydration levels affect endurance.

When working out hard and sweating profusely, people should also consume enough sodium to replace the salt lost from sweating.7,8 And if you are working out hard for 60-90 minutes or longer, add glucose as well.2,6,8 “Salt and glucose in the right percentage help escort water into your cells,” Oppezzo said.

Canva Pro Images

As mentioned, it’s also important to hydrate slowly.6,8,10 “If you flood water into your system by pounding it, it’s not going to get into the cells,” Oppezzo said. Instead it will slosh around in your digestive system and then you’ll just pee it out.10

And don’t worry about moderate caffeine consumption. It’s unlikely to cause dehydration during exercise.

Training Tip

Hydration isn’t one-size-fits-all. While general guidelines exist, your needs depend on your body, sweat rate, and sport. To perform your best, learn your sweat rate and personalize your approach. Remember, what works for others may not work for you — hydrate based on your unique needs.

Personalizing the Guidelines

Although general hydration guidelines might apply to some theoretical average person, they need to be personalized to meet your needs based on your body type, your sweat rate, and the demands of your sport.2,7,11

Some in the sports medicine community believe people can rely on their thirst drive to stay hydrated, while others recommend having a personalized hydration plan.1

Canva Pro Images

The problem with trusting your thirst drive: It isn’t always reliable,1 and it becomes less so with age.10,12 The problem with a personalized hydration plan: It might be unnecessary for people who do have a reliable thirst drive, and some people might go overboard trying to tailor their hydration in ways that don’t matter or are even harmful.1

As with most things, there’s a middle ground: Trust but verify, Oppezzo said. For people who care about their athletic performance, this means developing a good understanding of your own sweat rate. There are laboratory tests for measuring sweat rate,13 but many are impractical for most people to use, Oppezzo said. The most user-friendly approaches: Urine color and weight-based sweat rate.

A good basic test of hydration: Check your urine color in the morning. If it’s dark yellow, it’s a good idea to drink more water.7 But keep in mind, vitamins and medications can also darken urine, Oppezzo said. And urine color doesn’t immediately reflect what’s happening at the cellular level, so use it cautiously in acute situations.13

Canva Pro Images

To determine your sweat rate, weigh yourself naked after peeing and before exercise, and then do the same after exercise.7,8,10,13 “When you weigh yourself before and after the workout, that’s not fat you lost, that’s water,” she said.

Of course, you need to also account for what you ate and drank during that time and any bowel movements. These would all alter your weight. And be sure to test your sweat rate in different environmental conditions, including heat, cold, and humidity. Research has shown that sweat rate can vary by 8-12% even in the same conditions, and can jump dramatically in the heat.5 Once you know how much water you lose under the conditions you’ll likely face during a competition, you can create a plan to replace those losses during and after the event, Oppezzo said.

Did You Know?

One way we lose water during exercise is through exhalation: The millions of tiny air sacs (called alveoli) inside our lungs have a surface area the size of a racquetball court.15

People who rely on their thirst drive and don’t lose much weight during workouts are likely doing a good job replacing their water loss, Oppezzo said. They may be fine without a personalized hydration plan. But, “if you’re seeing 2% weight loss you probably need to get a hydration plan going, because that’s when you start to see some of the symptoms that affect performance,” she said.

Canva Pro Images

Oppezzo’s own experience with dehydration and hyponatremia has taught her a few lessons. One obvious one is to not get dehydrated in the first place. If she’s doing a crazy hard workout in heat, she makes sure to bring water as well as electrolyte replacements. And if she ever finds herself dehydrated after a workout in the future, she knows to eat a handful of pretzels or slurp some chicken broth. Anything with some salt would have made a big difference, she said. “I should have just had soup.”

Get Deeply Researched Insights on Human Performance

Join our mailing list to get actionable performance tips and nuanced explanations of the science.

Citations

- Burke, L.M. (2021) Nutritional approaches to counter performance constraints in high-level sports competition. Experimental Physiology. 106(12): 2304-2323.https://doi.org/10.1113/EP088188

- Fallowfield, J. L., Williams, C., Booth, J., et al. (1996) Effect of water ingestion on endurance capacity during prolonged running. Journal of Sports Sciences. 14(6): 497–502. https://doi.org/10.1080/02640419608727736

- Deshayes T.A., Pancrate T., Goulet E.D.B. (2022) Impact of dehydration on perceived exertion during endurance exercise: A systematic review with meta-analysis. Journal of Exercise Science and Fitness. 20(3):224-235. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jesf.2022.03.006

- Pellicer-Caller, R., Vaquero-Cristóbal, R., González-Gálvez, N., et al. (2023) Influence of exogenous factors related to nutritional and hydration strategies and environmental conditions on fatigue in endurance sports: A Systematic Review with Meta-Analysis. Nutrients. 15:2700. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu15122700

- Smith J.W., Bello M.L., Price F.G. (2021). A case-series observation of sweat rate variability in endurance-trained athletes. Nutrients. 13(6):1807. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu13061807

- Kerksick, C.M., Wilborn, C.D., Roberts, M.D., et al. (2018) ISSN exercise & sports nutrition review update: research & recommendations. Journal of the International Society of Sports Nutrition. 15:38. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12970-018-0242-y

- McDermott B.P., Anderson S.A., Armstrong L.E., et al. (2017) National athletic trainers’ association position statement: fluid replacement for the physically active. Journal of Athletic Training. 52(9):877-895. https://doi.org/10.4085/1062-6050-52.9.02

- Sawka, M.N., Burke, L.M., Eichner, E.R., et al. (2007) American college of sports medicine position stand. Exercise and fluid replacement. Medicine and Science of Sports and Exercise. 39(2):377-90. https://doi.org/10.1249/mss.0b013e31802ca597

- Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health DHHS (NIOSH) Publication No. 2017-126CDC, Heat Stress Hydration handout. https://www.cdc.gov/niosh/mining/userfiles/works/pdfs/2017-126.pdf

- Casa, D.J., Clarkson, P.M., Roberts, W.O. (2005) American College of Sports Medicine roundtable on hydration and physical activity: consensus statements. Current Sports Medicine Reports. 4(3):115-127. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.CSMR.0000306194.67241.76

- Belval, L.N., Hosokawa, Y., Casa, D.J., et al. (2019) Practical hydration strategies for sports. Nutrients. 11(7):1550. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu11071550.

- Begg D.P. (2017). Disturbances of thirst and fluid balance associated with aging. Physiology and Behavior. 178:28-34. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.physbeh.2017.03.003

- Barley, O.R., Chapman, D.W., Abbiss, C.R. (2020) Reviewing the current methods of assessing hydration in athletes. Journal of the International Society of Sports Nutrition. 17:52. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12970-020-00381-6

- Muñoz-Urtubia N., Vega-Muñoz A., Estrada-Muñoz C., et al. (2023) Healthy behavior and sports drinks: a systematic review. Nutrients. 15(13):2915. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu15132915

- Combs M.P., Dickson R.P. (2020) Turning the lungs inside out: the intersecting microbiomes of the lungs and the built environment. American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine. 202(12):1618-1620. https://doi.org/10.1164/rccm.202007-2973ED

Playbook Terms of Use & Copyright

©2023-2024