Coffee, Gels, Energy Drinks: Which Source of Caffeine is Ideal for You?

With so many caffeine choices out there, which one is best for your fitness and athletic goals? We chatted with Dr. Burke to discuss the pros and cons of various caffeine sources, and what to look for when choosing a caffeine source.

April 10, 2024

Louise Burke, PhD

Dr. Louise Burke is a Professorial Fellow at the Australian Catholic University. She is a distinguished sports dietitian known for her extensive experience counseling elite athletes. She has worked at the Australian Institute of Sport for 30 years and was the team dietitian for the Australian Olympic Teams for the 1996-2012 Summer Olympic Games. She was awarded a Medal of the Order of Australia for her contribution to sports nutrition.

Do you enjoy the ritual comfort of a warm brewed coffee or do you prefer the quick-fix of energy gels and sprays? Do you know how many milligrams of caffeine you consume daily?

Caffeine can be a valuable performance ally if chosen wisely. We all have varying sensitivities to caffeine, and the optimal amount for one person may differ from another. Tracking your caffeine intake can allow you to identify the amount that gives you the best performance kick without the negative side-effects like jitteriness, increased heart rate, or disrupted sleep.

But a significant challenge emerges — knowing precisely how much caffeine you are consuming. Unlike food labels that disclose nutritional content, determining the caffeine dose in coffees, energy drinks, sprays and other products is less straightforward.

Canva Pro images

In general, the ideal intake of caffeine for athletics is a small dose of caffeine when fatigued. Putting a number to this, the recommendation is around 3 mg/kg, which translates to about a 200mg caffeine pill for a 150-pound individual.

“You want the maximum performance effect with the least amount of caffeine, but figuring out how much caffeine you’re getting can be tricky,” said Dr. Louise Burke.

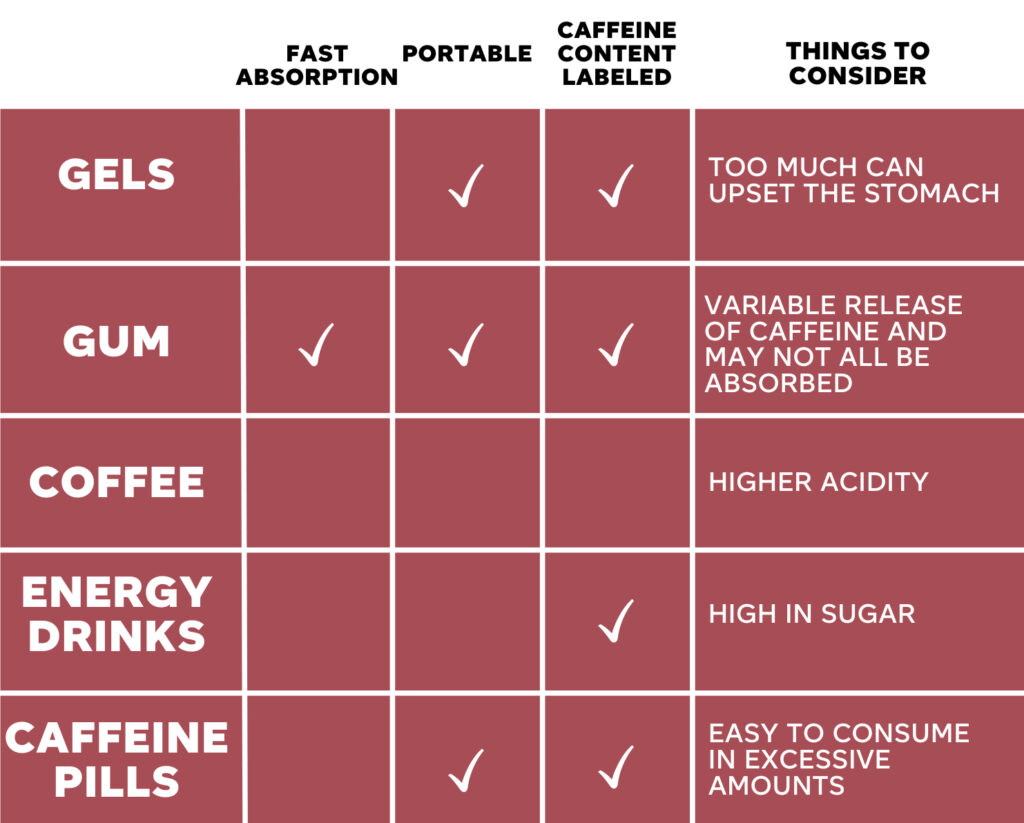

Many pre-workout supplements, for example, hide the exact caffeine content behind proprietary blends, making it challenging for consumers to know what they are putting into their bodies. On the other hand, many gums and gels often provide a more transparent caffeine content, allowing users to better control their intake. Let’s take a look at some of the options.

Caution

While it’s commonly known that coffee and many teas contain caffeine, there is the potential presence of ‘hidden’ caffeine in unexpected sources. Products such as soda, chocolate, energy bars, medications, ice cream, and even certain coffee-flavored foods and specialty wines may also contain caffeine. It’s advisable to be mindful of your overall caffeine intake, especially if you are sensitive to its effects or trying to limit your consumption.

Adobe free images

Caffeinated Gels and Chewing Gum

Caffeinated gels are often clearly labeled and pre-packaged, making them a portable option for on-the-go performance.

“A caffeine gel may also offer additional benefits like carbohydrates that make them suitable for specific performance goals,” said Dr. Burke.

If you participate in an endurance sport like long-distance running or cycling, these caffeine gels – packed with carbohydrates – serve as both a fuel and a way to combat fatigue.

Or perhaps you want an instant energy kick? Try caffeinated chewing gum, said Dr. Burke. The caffeine in the gum is absorbed across the cheek cells and enters the bloodstream faster than a caffeine pill,1,12 which has to pass through the digestive system first to reach the bloodstream. Taking caffeinated chewing gum minutes before or during an activity, with a dose between 100–300 mg, has been shown to boost both aerobic and anaerobic performance.1

Do all aerobic and anaerobic activities have performance benefits from caffeinated gums?

There’s not enough evidence yet to make that broad claim. When it comes to aerobic performance, studies have specifically examined cycling times, while anaerobic performance was assessed through shot-put distance, counter-movement jump heights, and sprint cycling times.

You may have caught the fact that the caffeine dosage for gum isn’t given in mg/kg. It’s harder to control dosing with gum. In one study, caffeinated chewing gum containing ∼50 mg of caffeine had a similar absorption rate with instant coffee of the same strength. However, the caffeine exposure with the gum was 18% lower (41 mg) than the intended original dose. This discrepancy was likely due to the fact that not all of the caffeine was released from the gum during chewing.9 Research suggests that around 80% of caffeine is released during 5 minutes of chewing, and if you chew for 10 minutes, around 90% is absorbed. Of course, individual differences may influence the release, especially the less time you spend chewing.12

Canva Pro images

Caffeinated Nasal Sprays

In recent years, the world of caffeine has witnessed a novel entry – caffeinated nasal sprays. In a small trial, there were no significant improvements in either a 30-second all-out cycling performance test or a 30-minute time-trial performance when using 15 mg/mL caffeinated nasal sprays.10 There are few investigations into the effectiveness of nasal sprays and more research in diverse populations is needed.1,2,4,5

Caffeine from Energy Drinks, Coffee, and Tea

While most energy drinks clearly list the amount of caffeine they contain, caffeine from sources like coffee and tea could be a healthier option for everyday consumers, especially compared to energy drinks that are often packed with sugar.7 A single 16-oz energy drink typically contains 54 grams of sugar (about 1/4 of a cup of sugar).11

Some athletes may not enjoy the acidity of coffee and tea. In this case, athletes can either use milk to neutralize some of the acidity or opt for a gel instead. Keep in mind that coffee additives like cream and sugar are calorie-dense and dietary guidelines advise moderation.

How much sugar per day is recommended?

The World Health Organization (WHO) recommends reducing added sugar due to evidence that links added sugar consumption to poor health. WHO urges consumers to limit their consumption of “free sugars” to less than 10% (and ideally less than 5%) of their total daily energy intake, which translates to approximately 50 grams (12 teaspoons) per day for a 2,000 calorie diet.8

It’s tough to know how much caffeine you get in a cup of coffee though. Caffeine levels in coffee can differ based on the type of coffee beans and the brewing techniques used. One study of 20 commercial espresso coffees found a 6-fold difference in caffeine levels.3 Another study conducted in Australia investigated 97 espresso samples from various vendors in five major shopping centers and found a caffeine content ranging from 25-214 mg per serving.6

Training Tip

Caffeine content varies among different coffee types and brewing methods. If you want an exact caffeine dosage, find products that provide the milligram per dose. Next, consider when you need the caffeine. If you need caffeine as a pick-me-up during an athletic event, consider using well-labeled, packaged caffeinated gels or gum.

Navigating the caffeine landscape involves considering personal preferences, training needs, and health considerations. Whether it’s the ritual warmth of a cup of coffee or the convenience of a packaged gel, athletes are encouraged to experiment and find the ideal caffeine source for them.

Canva Pro Images

For more on caffeine and physical performance, read “What’s the Optimal Timing of Caffeine for Physical Performance?”

Get Deeply Researched Insights on Human Performance

Join our mailing list to get actionable performance tips and nuanced explanations of the science.

Flash Q&A with Dr. Louise Burke

Do you drink caffeine?

Even though I’ve written a book on caffeine, I actually have quite a low caffeine intake. I do not drink coffee. I love the smell but hate the taste. Most of mine comes from cups of tea. I target my use around my exercise.

What’s exciting to you about research in the field right now?

The female athlete angle is exciting because I think it’s high time that we got some quality research as well as quantity. Another aspect of caffeine research I’m excited about is that we’re getting better at doing studies in real life competitions with high-level athletes. Now we’re really getting to the bottom of some of the questions and answers that we want.

Favorite activity to stay fit?

I’m running marathons at the moment. I used to do ironman triathlons, but I’ve gone back to just running. I’m finding I’m not getting slower as I age, so I’ve gone from being an okay athlete to being good for my age. Now I’m using all my sports nutrition strategies on myself.

Favorite marathon?

New York City Marathon

Citations

- Guest N. S., VanDusseldorp T. A., Nelson M. T., et al (2021). International society of sports nutrition position stand: caffeine and exercise performance. Journal of the International Society of Sports Nutrition. 18(1). https://doi:10.1186/s12970-020-00383-4

- Wickham K. A., Spriet L. L. (2018). Administration of caffeine in alternate forms. Sports Medicine. 48(1), 79-91. https://doi:10.1007/s40279-017-0848-2

- Crozier T. W. M., Stalmach A., Lean M. E J., et al. (2012). Espresso coffees, caffeine and chlorogenic acid intake: potential health implications. Food & Function. 3(1), 30-33. https://doi.org/10.1039/C1FO10240K

- De Pauw K., Roelands B., Van Cutsem J., et al (2017). Electro-physiological changes in the brain induced by caffeine or glucose nasal spray. Psychopharmacology. 234, 53-62. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00213-016-4435-2

- De Pauw K., Roelands B., Van Cutsem J., et al (2016). Do glucose and caffeine nasal sprays influence exercise or cognitive performance? International Journal of Sports Physiology and Performance. 12(9), 1186-1191. https://doi.org/10.1123/ijspp.2016-0598

- Desbrow B., Hughes R., Leveritt M., et al (2007). An examination of consumer exposure to caffeine from retail coffee outlets. Food and Chemical Toxicology. 45(9), 1588-1592. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fct.2007.02.020

- Al-Shaar L., Cercammen K., Lu C., et al (2017). Health effects and public health concerns of energy drink consumption in the United States: a mini-review. Front Public Health. 5(225). https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2017.00225

- “Who guideline : sugar consumption recommendation.” World Health Organization. www.who.int/news-room/detail/04-03-2015-who-calls-on-countries-to-reduce-sugars-intake-among-adults-and-children. Accessed 30 Jan. 2024.

- Sadek P., Pan X., Shepherd P., et al. (2017). A randomized, two-way crossover study to evaluate the pharmacokinetics of caffeine delivered using caffeinated chewing gum versus a marketed caffeinated beverage in healthy adult volunteers. J Caffeine Research. 7(4):125-132. https://doi.org/10.1089/jcr.2017.0025.

- De Pauw K., Roelands B., Van Cutsem J. et al. (2017). Do glucose and caffeine nasal sprays influence exercise or cognitive performance? International Journal of Sports Physiology and Performance. 12(9): 1186-1191. https://doi.org/10.1123/ijspp.2016-0598

- Higgins J. P., Tuttle T. D., Higgins C. L. et al. (2010). Energy beverages: content and safety. Mayo Clinic Proceedings. 85(11): 1033-1041. https://doi.org/10.4065/mcp.2010.0381

Check food and beverage labels for up-to-date information

The sugar content of energy drinks is based on a publication from 2010, and it’s worth noting that the sugar levels in the drinks may have changed since then.

- Morris C., Viriot S. M., Farooq Mirza. Q. U. A., et al. (2019). Caffeine release and absorption from caffeinated gums. Food & Function. 10(4): 1792-1796. https://doi.org/10.1039/C9FO00431A

Playbook Terms of Use & Copyright

©2023-2024