Foundation AI model is transforming analysis of walking and running dynamics

Collaborators

Biomechanics labs can take hours and cost thousands of dollars to analyze a single patient. GaitDynamics analyzes movement and predicts joint forces a thousand times faster than traditional methods.

By Kristy Hamilton

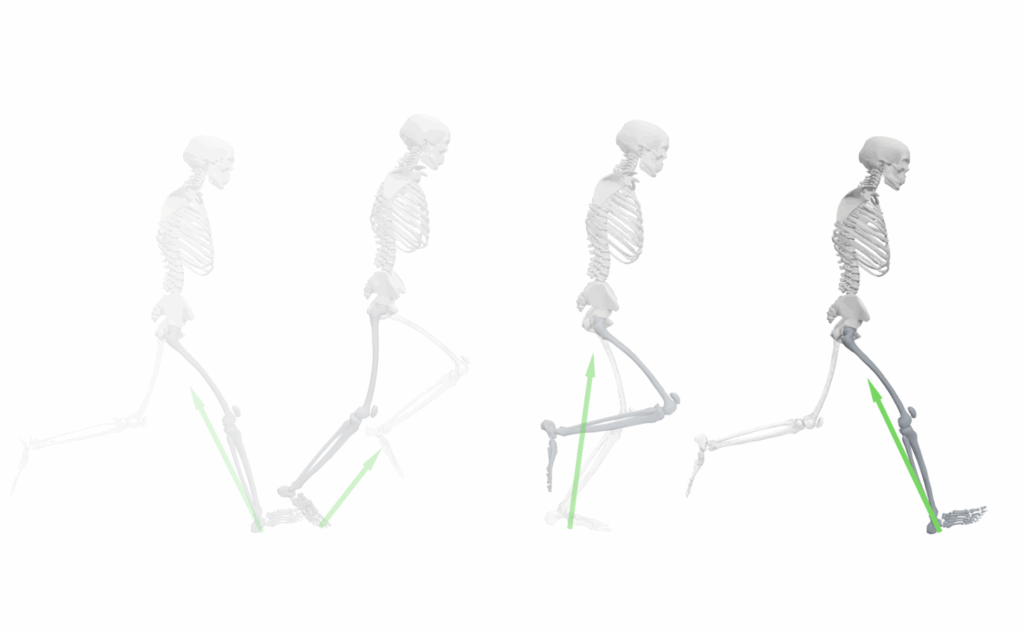

A new foundation AI model generates running motion and ground reaction forces (green arrows). Screen capture from video provided by Tian Tan.

Inside a biomechanics lab, a ring of cameras track subtle shifts of the body while sensors measure the forces generated with each step. These facilities provide valuable information for a wide range of applications: helping runners adjust their form to reduce stress on their knees, assessing walking patterns in children with cerebral palsy, or testing interventions for recovery after stroke. But the process can take hours and cost thousands of dollars to collect all the data needed for analysis.

A new AI model from the Wu Tsai Human Performance Alliance and Stanford University aims to change that. The tool, called GaitDynamics, analyzes the walking patterns of a single patient, and predicts the forces through their joints, all with high speed and flexibility. Researchers published their findings this month in Nature Biomedical Engineering.

The potential applications range from clinical care to coaching. “Our study demonstrates a broader utility compared to prior AI models that are task-specific,” said lead author Tian Tan, a research engineer at the Wu Tsai Human Performance Alliance at Stanford. “We demonstrated data-driven models’ feasibility in helping clinicians identify optimized gait patterns for better knee joint health, as well as in assisting running coaching to improve speed, without comprehensive testing of conditions.”

A Thousand Times Faster

Traditional physics-based simulations can model human movement in detail, but they demand enormous computational power. Simulating just a few seconds of walking might tie up a computer for hundreds of hours.

GaitDynamics slashes that time dramatically. The model produces a 1.5-second gait trial in under one second on a standard laptop. This is roughly a thousand times faster than existing methods. The speed comes from a diffusion model, the same AI architecture that powers image generators. But instead of conjuring pictures from random noise, GaitDynamics learns to generate biomechanical movement.

“Our study demonstrates a broader utility compared to prior AI models that are task-specific.”

“Physics-based simulation can be very useful in analyzing human movement and identifying strategies for applications such as joint load reduction, but its slow speed has traditionally constrained the scale of studies,” said Tan. “GaitDynamics can enable systematic human movement analyses at high resolutions that were previously infeasible.”

Though other AI models, like GEM and MotionGPT, can also generate realistic motion, their use case is for animation and gaming, focusing on how movement can be generated from modalities such as text. GaitDynamics, by contrast, is able to predict biomechanical forces like joint loads and ground reaction forces that matter for injury prevention and rehabilitation.

In practical terms, researchers can now explore many more “what if” scenarios. What if an athlete shortened their stride? Leaned forward slightly? Landed softer? GaitDynamics can help identify the combination most likely to protect a knee or save seconds in a race.

“Researchers may see the complete picture of how different movements work together,” said Tian, “allowing them to uncover the optimal strategy that maximizes the outcome.”

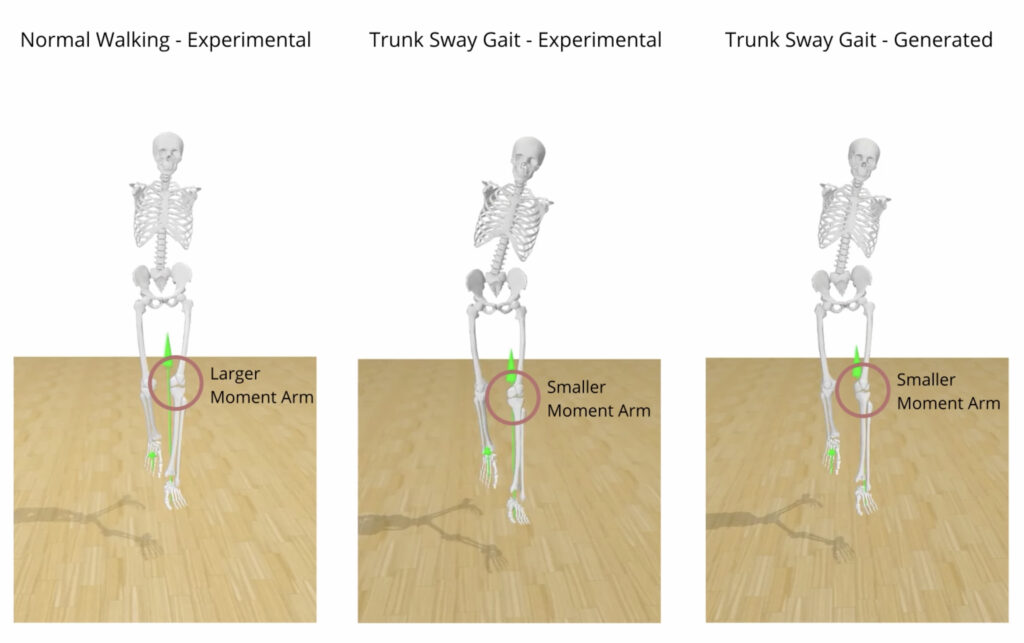

GaitDynamics accurately predicted the effects of a trunk sway gait modification strategy. Green arrows show the magnitude of the knee adduction moment (which “pushes” the knee inward) while walking normally versus walking with exaggerated side-to-side trunk sway. Large knee adduction moments are associated with knee osteoarthritis and are a common target of gait retraining. GaitDynamics predicted a smaller moment arm during the trunk sway gait, matching what was observed experimentally. Screen capture from video provided by Tian Tan.

Why Diversity Matters

The model owes its power to a diverse training set. While earlier AI systems learned from small datasets, GaitDynamics trained on a subset of the AddBiomechanics Dataset, which contains more than 70 hours of movement data across 15 research studies.

“Integrating data from multiple studies exposes the model to diverse conditions, such as variations in gait patterns, footwear, and speeds,” Tan said. “Such heterogeneity allows GaitDynamics to learn a generalized representation of human gait, as well as prevents it from overfitting to the specific protocols or measurement biases inherent to any single laboratory.”

That diversity paid off in unexpected ways. Even though the researchers trained GaitDynamics on healthy participants, the model maintained its accuracy when they tested it on people with knee osteoarthritis.

“GaitDynamics can enable systematic human movement analyses at high resolutions that were previously infeasible.”

“Initially, that was surprising,” Tan admitted. “But after looking closer at the data, we found that the gait patterns of osteoarthritis patients remained similar to those of healthy individuals, with the main difference being a slower walking speed.”

The model did stumble, however, when confronted with more dramatically altered movement patterns. “Accuracy dropped when we applied it to gaits that diverge much more significantly, like those seen in individuals post-stroke,” Tan said.

Filling in the Gaps

One of GaitDynamics’ strengths is how it handles the messiness of real-world data, which rarely arrives clean and complete. Body segments are blocked from camera view. Sensors malfunction. Motion-capture markers fall off.

GaitDynamics uses a technique called inpainting to fill in the missing information based on patterns learned during training. When the researchers deliberately withheld all hip data, accuracy dipped by only about 2 percent. Baseline methods to fill in missing data, by comparison, introduced errors ranging from 3.8 percent to more than 30 percent.

GaitDynamics is being used to control an exoskeleton as part of an on-going research project at the Wu Tsai Human Performance Alliance. Image captured from video taken by Six Skov and edited by Tian Tan.

What Comes Next

The team has released their data, demo, code and trained models to the public, inviting the research community to build on their work. And Tan and collaborators are developing applications for GaitDynamics.

“Before GaitDynamics can be deployed for clinical intervention or sports coaching, it needs to be tuned with data from elite athletes and clinical populations,” he said. “That’s a goal we’re actively working towards.”

Researchers at the Wu Tsai Human Performance Alliance and collaborators are pushing the analysis deeper, examining joint moments, contact forces, and the stresses on individual tissues. The long-term vision builds directly on GaitDynamics’ speed and flexibility—to one day be able to use it for AI-driven gait optimization for athletes and patients, and ultimately to embed the model into wearable technologies to guide assistive devices in real time.

Co-authors include Tom Van Wouwe, Keenon Werling, Karen Liu, Scott Delp, Jennifer Hicks and Akshay Chaudhari.

This work was supported by the Joe and Clara Tsai Foundation through the Wu Tsai Human Performance Alliance, and by the US National Institutes of Health (NIH)

Latest News

January 7, 2026

Foundation AI model is transforming analysis of walking and running dynamics

December 10, 2025

Study suggests how eccentric resistance exercises might strengthen tendons

November 21, 2025

Recordings Now Live: Female Athlete Research Meeting 2025

Get Engaged

Join our mailing list to receive the latest information and updates on the Wu Tsai Human Performance Alliance.